where

When you’re lying there in the stillness after dark, before you drift off to sleep, and your life is finally quiet, your field of vision blank.

When the world seems both possible and impossible.

When everything from the days before and coming starts sliding in and out of you.

When your body is aware of the texture of fabrics around you, your skin high on giving in.

Where does your mind go?

a perfect design

I cannot believe God plays dice with the universe.

— Albert Einstein

I once came across a display in an exhibit called Mathematica at the Center of Science and Industry (COSI) that left me in awe.

It consisted of two large panels of glass with evenly spaced horizontal rods running through them. Beneath each column of rods was a rectangular chimney with its two dark sides perpendicular to the glass.

A red line on the glass had the shape of a bell curve — a curve that rises slowly at first, then rapidly to a peak. It descends just as quickly before ending in a perfectly symmetric pattern.

At the top center of the case, hard dark balls fell one at a time onto the rods, bouncing from one to another. A ball hitting the rod directly beneath the opening was equally likely to bounce left or right. It was less likely to hit a second, lower rod, and less likely still to bounce in the same direction two or more times in a row.

I understood this. No human or machine controlled the balls’ motion. They fell at random. Yet this perfectly random motion filled the chimneys in the perfect pattern of a bell curve.

A bell curve was created by chance.

That astounded me. Mindless, inanimate matter moving by chance created an elegant form. It did so every time the chimneys were emptied into a hidden well and the balls started falling against the rods again.

I became overwhelmed with a realization that has stayed with me ever since:

Chance is not chaos.

Isaac Newton worked out the clockwork of the heavens. He believed that it could not exist without a clockmaker.

And he’s right.

All the patterns of nature result from mega-trillions of random events. The myriad cells in the human brain ultimately act randomly and are the product of random gene mutations, giving rise to a pattern, a history of decisions, a life, and a soul.

The material and the nonmaterial have been wedded from the beginning of the universe. Metaphysically, the properties of an entity are simply the patterns formed by the boundary that separates it from other entities, allowing it to be distinguished. A general property embracing a multitude of entities crosses its boundaries, making them indistinguishable and invisible to sensory perception, which operates by discriminating boundaries.

General properties are thus invisible to the senses. An example of a general property is the square root of two. Another example is the binomial distribution, which can be generalized and made concrete by drawing a bell curve.

General properties are perceived through general properties of brain cells, commonly known as thoughts. Thoughts that lead to successful interaction with the world are considered true. There are infinitely many general properties, but the only valid ones for us are those that allow us to interact successfully with the material world. The internal laws of thought (logic) are the preferences evolution has given our minds.

Since evolution acts through the world, we assume that logic is a valid guide in interacting with the world. Thoughts range far beyond the particulars of the world, which means, on the one hand, that thoughts can follow along useless or dangerous lines, but on the other, that thoughts can lead to innovation, and the creation of new realities.

Intelligence is inherent; there are signs of it everywhere. But it’s rare for intelligence to be internalized in individual organisms, so we need not assume their presence every time we see signs of intelligence, as in the clockwork of the heavens.

Yet, we exist in nature. Because nature’s intelligence is internalized in us, it is inescapable to conclude that we have an important role to play in the destiny of the universe.

It’s not guaranteed that we will survive to play such a role. Life may triumph in the universe and still perish on Earth. But while our potential doesn’t make us immune to the perils of the universe, it does give us reason to believe in ourselves, reason to accept human desires as reflective of tendencies inherent in nature.

Yes, chance is not chaos. God tells us that.

And I, for one, am listening.

a beautiful life

Life is beautiful. Not always, to be sure, but the moments of beauty and peacefulness exist, I think, to remind us that there’s much more perfection in each moment and within us than we usually realize.

Throughout the first part of the year, I’ve observed many different reactions to the good aspects of life. Those who are acutely conscious of the pain of others and the dire situation of the world, and our role in making it so, tend to feel guilty and allow this sense of shared suffering to gray out the happiness and good fortune they may feel. Others who are more self-centered have reacted by gradually habituating to an ambiance that ranges from anxiety and helplessness to obsessive fear regarding just about everything that has an element of risk — which comes to be life itself. And at the far extremes are those who react by hoarding what they have, trying to amass more, and justifying their belief that they’re deserving and others aren’t.

Should we suffer because other people are suffering more? Yes, would be the short answer: that’s what compassion means. But when we lose the capacity to see beauty, to wonder at the simple things life gives us for free, and to be renewed and to grow in understanding of what it means to have this gift of a human life … well, then I think something’s gone wrong. We survive because there are natural periods of coolness, wholeness, and ease. In fact, they last longer than our grasping and fear. This is what sustains us.

As much as I never thought it possible, in some ways my lack of vision has proven to be a gift. Not being able to see well (or at all, at times) has forced me to listen to and hear things that most others don’t, and it’s created a much greater sense of mindfulness and contemplation during the day. It’s also greatly enhanced my morning prayer routine, as I’m always aware that there’s much for which to be grateful, not least of which is the day ahead of me.

Prayer allows me the time to hold in my heart and mind, by name and image, all those I want to think about with special intention. The moment I get on my knees, I’m humbled by a spaciousness that’s, of course, already there but masked by thoughts, restlessness, and dissatisfaction. My low vision makes it possible to quickly settle into those precious moments when I do see the raspberries, smell the fragrance of the basil, and taste the salty dense tomatoes studding the loaf of bread.

And lest we think that the less fortunate on Earth are incapable of experiencing the same thing, I’m reminded of various conversations I’ve had with my friend Otan, a man younger than I who has spent much of his life working among the peasants of Africa and South America. Listening to him say that he’s never been around as much joy as he is with those folks who have so very little will forever be one of the greatest lessons I’ve learned about my own poverty and ignorance.

At the core, we’re all the same, and sooner or later all our defenses are stripped away. Those moments of rest and wholeness are free and aren’t dependent on other people, health, wealth, or even love. They’re there, I think, to teach us something.

Earlier today I had a conversation with a retinal surgeon who’s perfecting a treatment for macular degeneration, which could in turn be of great benefit to those of us with similar disease pathologies. I’m eager to learn, curious about what these moments will teach me, and wondering how all of this will define the human I’ve yet to become. While there’s no way to know what lies on the other side of this possibility, my faith ensures me that I'll be fine, regardless of the outcome.

There will undoubtedly be more later.

truth

When I was a little girl, I always believed that the summer came twice. It came with a classroom party to celebrate the end of the school year, but it came quietly in a dream the midnight before, too, when I’d rise from my bed, light a small candle, and watch the stars at the window, the silhouette of the huge oak and maple trees partly obscuring my view. Summer came in the quiet dreams of midnight, in the flame of an ordinary white candle, in waiting and wordless silence while the adults prepared for our final day, and in just breathing all that was.

Now life is fragmented across households and states, and yet another centerpiece of our family is sadly missing. This has already been a most difficult year, and I have to admit that I’ll be glad to see it come to an eventual end. Still, for all the grief and uncertainty, for all the adjustments and renewals, it’s been a lifetime of learning packaged not-so-neatly into the form of life as we know it.

I have an appointment a bit later; consequently, I recognize that I may be a bit too introspective for the hour. Still, for better or worse, here I sit, realizing that what’s in my head and heart needs to be written. Not so much because somebody needs to read my thoughts, but because writing them down is like claiming a small victory.

All of this has me thinking about the various forms of love that we experience, and in which we participate.

It seems to me that love is the only wisdom given to us. There’s no other. Love for all that is, love for another, love for self. There’s an honor, regard, awe, and endless gratitude in love. Love isn’t mere sentiment; love chooses, and love acts. Love isn’t selfishness or desire or need. Love doesn’t own another person’s dreams or attempt to dictate them.

Romantic love is intoxicating and sweetest of all, but it's a fleeting thing unless it’s founded on abiding friendship. It may indeed be Narcissus, infatuated with his reflection in the pool, reaching into the water to embrace only weeds and mud.

Friendship creates a space of hospitality and welcome for another, a shelter of acceptance, a place to come and be, a home for the heart where one can always return, where the door will always be opened, the light will be on, the hearth will be warm, and there will be sustenance and a word of care. Friendship is a gift.

One hard thing about a real gift is that it doesn’t imply an obligation on the part of another, even to receive it. Love has to suffer that, too. There’s no other way. One would think that the easier thing would be to cease to love, to decline to extend a gift that may refused, opened or unopened, or ultimately dashed from our hands by mortality itself. But to cease to love is folly. It’s emptiness. It’s all the salt in the Dead Sea that renders those waters poison to drink. Willingness to suffer and to lose is, therefore, a part of love and wisdom, because there can’t be love without risk of loss. Love deals pain as surely as it does joy, but the pain and the pleasure twined together remind us that we’re truly alive.

This is how Emily Dickinson closes a poem about friendship that abides:

And so, as kinsmen met a-night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.

I love these lines about the undying conversation friends have, and lovers, too, if they’re friends foremost. The wisest people in the world are those who know the value of friendship above all, and who make their friendships, especially those with great promise, a vital life’s work.

Platitudes fall like pattering raindrops on the roofs of our minds, then flow into the gutters we construct to carry them away. Truths, on the other hand, sear us like lightning that illuminates the heart of the storm.

What’s the difference between platitude and truth?

Often, only the living we’ve done and the chances we take.

bookworm

I’m quite tired this morning. It’s because I’ve gotten my days and nights mixed up again, a frequent consequence of my vision issues. It typically doesn’t make too much of a difference, except (for obvious reasons) on Sundays, but today seems a bit different somehow.

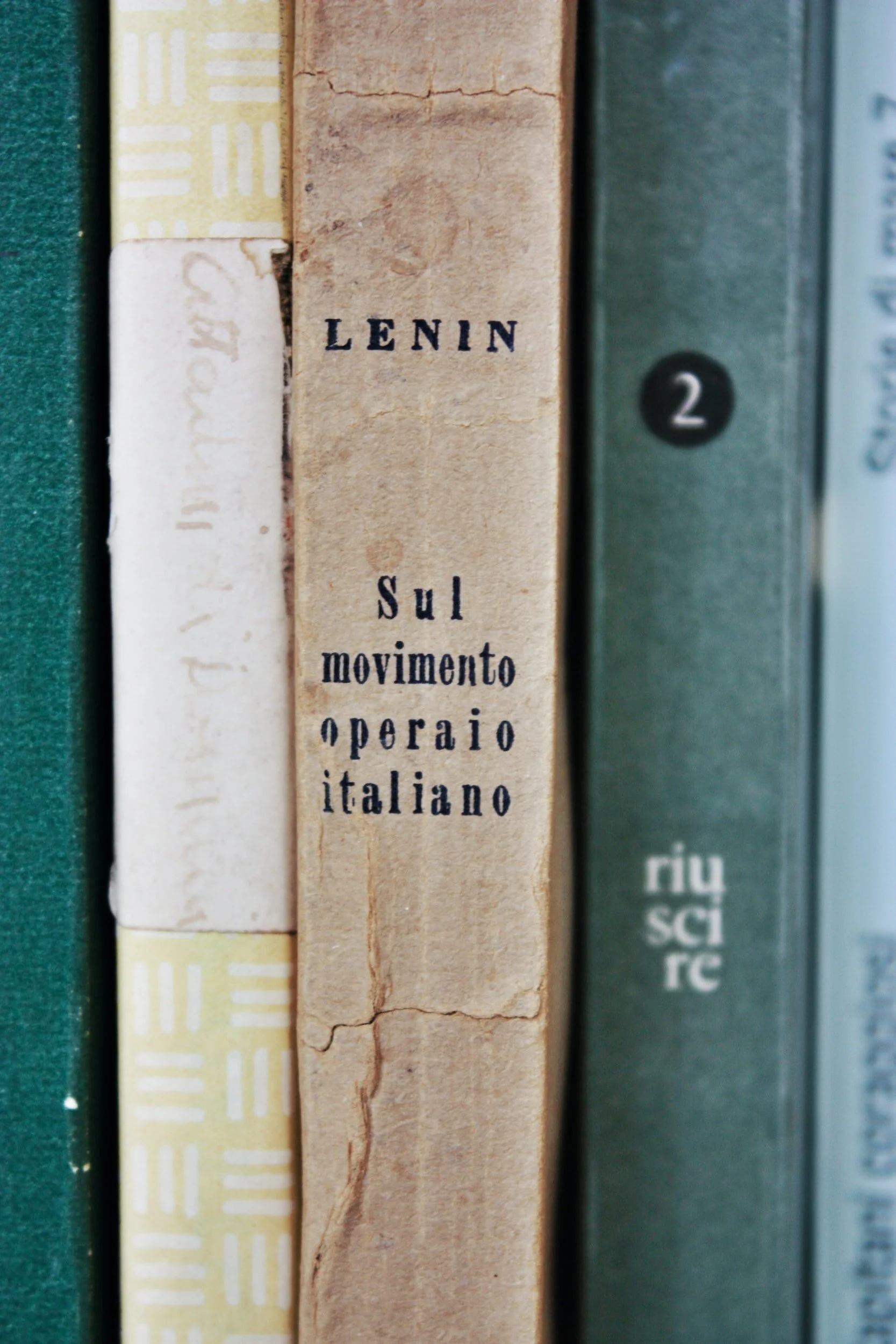

And so, I’m doing what I always do when I feel out-of-sorts: I’m looking for something to read. I run my fingers over books on the shelves, those markers that make me realize how quickly my life has passed. It’s been full, this life I’ve lived, as evidenced by the volumes that have captivated me. There’s the shelf of Greek books — the plays, philosophers, mythology, science; different translations of The Iliad and The Odyssey; books on Greek and Cycladic art. Ancient history. Plato. Virgil.

Those dark spines give way suddenly to French literature, then American; there’s William Carlos Williams underneath The Presocratic Philosophers. And my ever-present Kerouac lies atop the first volume of Vitruvius — On Architecture.

This is cheering me up already.

Beneath the French are the Russians, with the Germans off to the right. And, funny thing, on the deeper shelf underneath them, tilting a little like rock layers exposed along a road cut, are music scores representing most of Europe and the new world, along with a couple of books on anatomy and a few Braille manuscripts, stuck there because they’re the same height as the scores.

I’ve always been a voracious reader. Even as a child, I’d churn through book after book every week. I loved the power of the written words, and the way they’d take me on a journey through space and time, nearly always to destinations unknown. No matter where I went or what I was doing, there were always a few books and at least one journal that accompanied me.

I could stop right here and probably tell a story about any one of those books. Each has a specific reason for remaining, not least of which is as chosen companions and markers on this strange journey of my particular life, decade after decade. I’ve books that were given to me as gifts when I was in primary school, and others purchased decades later. And even though these books represent an intellectual journey to which I sometimes arrogantly attach great importance, the early ones were actually a pretty good predictor of what would end up on the shelves.

But now I’m standing here, running my fingertips over books whose stories have largely gone silent.

I’m thankful that I’ve learned Braille, but oh, how I miss the anticipation of picking up a beloved book and inspecting the covers before I begin to read. I’ve always loved the weight of the book in my hands, and the texture of the paper between my fingers as I turn the pages. There’s something very calming about the soft thwish of pages gently flipping as they bind the words into a story that’ll live forever.

Ça va sans dire.

Earlier, I listened to a slow movement from Tchaikovsky’s Barcarolle, then a bit from Bach’s Aria mit 30 Verδnderungen, BWV 988, ending with Variations 21-25, which I often play when someone dies. It’s a journey right into the heart of confusion and pain, and then it gradually untangles and comes to rest, even if the path to that place is still not especially comprehensible.

That piece has a lot of mystery in it for me because it takes me somewhere difficult and dark and undenied, carrying my doubts bundled on my back. When I emerge out of the woods, there’s not relief, exactly, but there’s a definite sense of having done something I needed to do. The music has accomplished something certain books do, too, in a totally different way.