shining forth

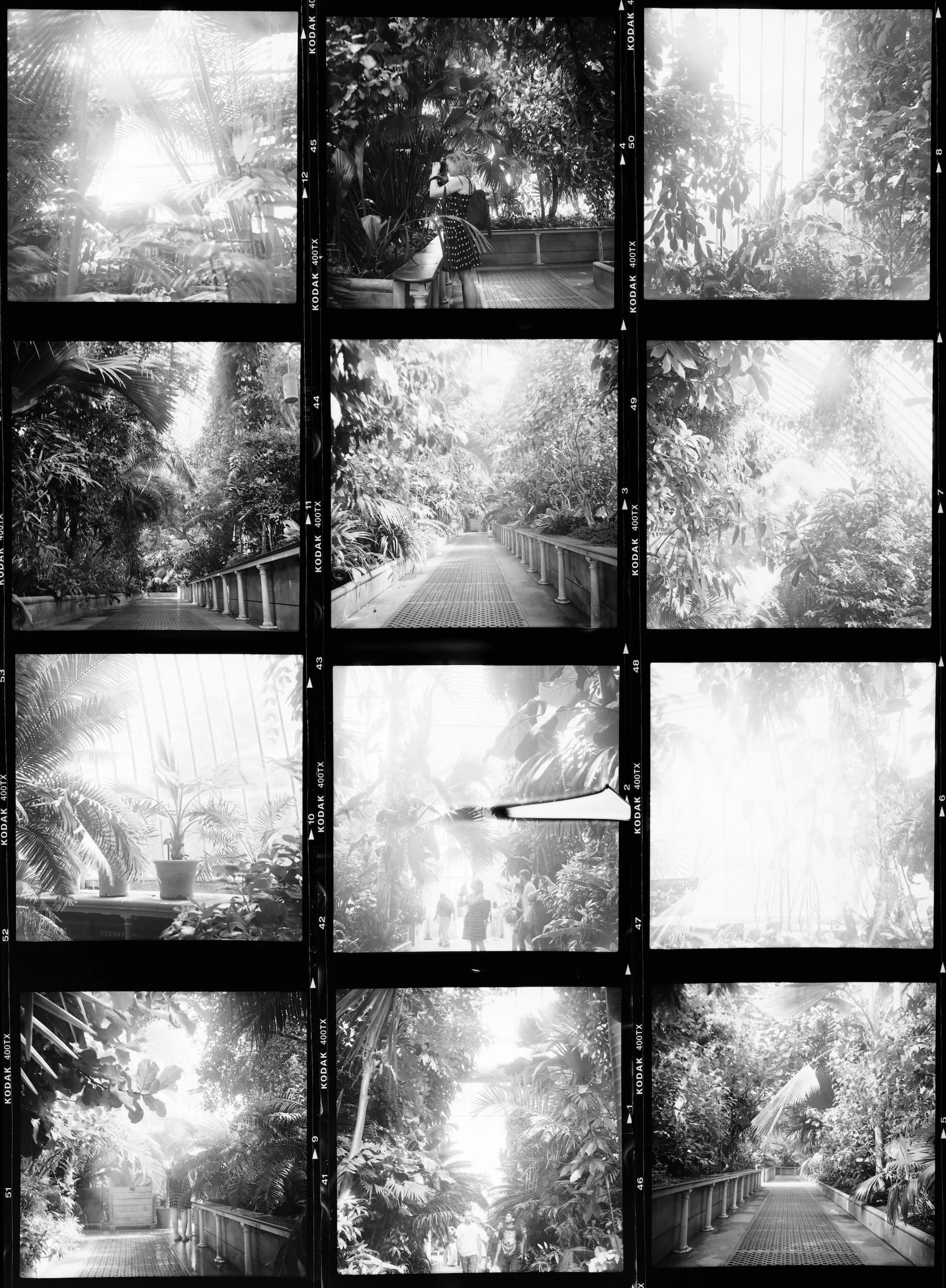

Long before iPhones and digital cameras, there was film. When you released the shutter to take a photograph, light reacted with the silver-halide particles in the film emulsion. Until the film was developed, it’d be an invisible reaction — and so she floated there, her image captured in darkness.

I make lists to remember.

She used to sit at the desk next to mine in the darkened lecture theatre as the professor ran images through the slide projector — Doric, Ionic, Corinthian columns, the caryatids of the Erechtheion. Sometimes she’d reach over and draw in the margins of my notebook: spirals reminiscent of Klimt. Eyes. Calculations of how many Drachma she would keep for souvenirs as we traveled through the Greek Islands. In return, I’d scribble cryptic messages, written in the International Phonetic Alphabet we learned in linguistics, when the lecture was dull: | sh ut mi |.

What we shared.

A large house that permitted us to live with four of our closest friends. A collage of black and white photographs of faces we’d snapped in the street, each one enlarged and cropped close so that their eyes and cheekbones filled the frame. Meals of pistachios and diet Coke. Cole’s electric kettle we’d fill to make jasmine and camomile tea. A maroon university sweatshirt with a hole in the left sleeve. Michelle’s expansive collection of operas and classical music. Gia’s massive professional video cassette recorder that I simply couldn’t rewind. Bret’s vinyls of Van Morrison. A bicycle pump. A sense of despair, that we had so little time.

A tiny dent I can still trace on the bridge of my nose, sustained when three of us crashed our bikes head-on as we peddled home from a late-night showing of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. A scraped knee. A cracked rib. Two hairline fractures in her left arm. I think she called out to us, or we to her, and we each turned in a wide, slow, graceful arc directly towards the other, colliding in the middle of the street. For some inexplicable reason, none of us was able to swerve out of the way. At first, I seemed to be the injured one, with blood pouring out of my nose, and a huge black gash under my chin. She and Cole wheeled the bikes home, he balancing one with each arm, patient as I limped slowly along beside them. Inside, Gia helped me rinse the blood out of my clothes before she insisted I go to bed. As she turned out the lights, she placed one cool hand on my forehead, and it seemed for a moment to still the pain. But she came to me later, in the middle of the night, pulling me out of the dark, out of a dream in which I wandered blindly through a labyrinth, inching forward with arms outstretched, afraid I would smash into a wall — “I think my arm is broken.” No moon that night. Lucid, luminous details return to me, intensified by the constant dull throb of pain in my head and the sudden plunge out of sleep. I can still feel the skin taut on my knee where the blood had dried. I remember the damp grass soaking into my sneakers and a shower of icy raindrops as I tore off a handful of sumac from a hedge outside the house. It must’ve rained in the night, while I slept. We walked along the empty sidewalks, along the paved path that runs through the medical buildings, slipping between the sulfurous pools of light along the way. There were stars overhead, glittering through the bare tree branches. Orion, Cassiopeia. In the emergency room, a nurse filled in a chart and led her away. I sat in a hard, plastic chair and waited. A radio played jazz quietly in the background. She came back two hours later, her arm tightly bound in a white cloth sling. Grinning, she held out her wrist to show me the plastic ID bracelet fastened there with a metal clip, spelling out her name in smudged purple letters, identified as female, blood type B negative.“He let me keep the x-ray of my arm.” Euphoric. “That’s why it took so long. They had to find a technician.”

“Does it hurt?”

“I can’t feel a thing.” She shook the bottle of painkillers the doctor had given her like a castanet as we retraced our path, the world filling in now as the dawn light grew, clumps of emerald moss between cracks in the pavement, the bright light of the hospital sign. People passed us heading for their morning meetings and lectures and commutes and I wondered if they could see us, if we walked invisible through an overlapping universe, jarred out of focus when we crashed into one another in the night. I bent down to pick up a worm stretched out swollen and purple on the asphalt and placed it gently in the soil. Back at the house, she asked me to tape the x-ray to the window. Radius. Ulna. Fine striations, our collision etched in the bone.

A weekend trip with all the roommates. On the plane, Gia’s seat neighbor showed her a photograph of Queen Elizabeth, resplendent in a blue cape, diamond-encrusted tiara, and wristwatch. Airplane food — two scoops of reconstituted egg garnished with a slice of orange and dry wheat toast. A woman arguing with the crew about checking her bicycle, trying to find room to place the carton filled with giant bunches of lychees and lavender, a tiny tortoise-shelled cat embroidered on the bag. The scent of lavender enveloped us as she wobbled past. Staring out the window into the various patches of land below, rock pools set deep in sandstone, a dark astronomical lens peering back through time.

A typology of stone. The night before her term paper was due, she stood in the center of her room surrounded by hand-drawn diagrams, lab reports, and the photographs from the trip, trying to piece them together. “I don’t think I can do this.” She looked up at me, then crouched down awkwardly, her arm still in a sling, to pick up a cross-section, leaving a gap of hardwood floor in the paper mosaic. I opened the window and the breeze smelled faintly of freshly cut grass; it rippled through the pages bleached of color in the dim light. I could see her face reflected in the mirror above her desk, concentrating, biting her lower lip. Her father had insisted she take geology as a minor, something to fall back on, the gravitas of stone. And she attended every lecture, getting up at seven in the dark winter mornings as I only wanted to lie in bed, deep under the covers in a cave of warmth, sometimes catching a glimpse of her shadow underneath my bedroom door as she walked through the hall, dressed in her brown corduroys, ragged at the hems and just an inch short so that her socks always showed, her cloth backpack crammed with books and slung across her navy wool jacket. Then I would fall asleep, waking again when I heard her return, her face always bright from cycling through the cool morning air. She took detailed, elaborate notes, carefully wrote up each lab, spent hours sitting at her desk, her head in her hands, studying the 600-page textbook. Once she showed me a Burgessia Bella, a dark round body with a skinny whip-like tail, embedded in gray stone. “My professor says it’s exclusive to the Burgess Shale in Canada — 530 million years old. It swam along the bottom of the sea and then one day it sank into the sediment and died. Isn’t it strange, that I can hold it here now, in my hand? It looks like a shadow burned into the rock. Somehow it survived.” She was especially interested in trace fossils — not the remnants of the animal but some record of its movement, burrowings, tracks, the imprint of a body, captured by a pocket of clay or mud and then baked hard by the sun or buried under layers of moss. It wasn’t the discovery that interested her, whether by accident or erosion, but more the knowledge of it lying there in the darkness, tremulous, secret. I think the idea of it being uncovered upset her, the earth sliced open by a sharp metal blade revealing the imprint, the exposure of something that should remain silent and numinous. It was better left sealed in the stone matrix, protected by thick layers of soil and clay.“I don’t think I can do this.” She studied the cross-section, passed it to me, bent down again, and reorganized a series of photographs. I looked at my watch — past midnight; panic had set in. It was always like this with her, panic needing to reach a certain critical mass, engulfing her, usually carrying me along with it, before the words came, still tortuous and slow. She preferred working by eye, by touch. She couldn’t sit still but needed to rearrange the pages of notes, feel the rock samples in her hands, scratch them with her fingernail, a penny, a nail, even taste them as if she could swallow their essence, her body always in contact with the hard surfaces.

It took all night; I sat cross-legged on the floor with her typewriter on my lap and typed up the report as she dictated it to me, making corrections, interleaving the typed pages with figures, and glossy photographs. The printer ran out of paper on page 17 and we had to make do with green-tinged sheets taken from her sketchbook. It came to sixty-two pages, “Profile: North American Geology,” a patchwork report fastened by a large butterfly clip. She asked me to type all the names in red capitals, to bold them so that they stood out sharply — SHALE LIMESTONE MICA QUARTZ. I remember the feel of their imprint as I ran my fingers across each completed page, garnet inclusions in a metamorphic rock.

Postcards she sent us over Christmas break, from her home in Seattle. Gandhi in a loin cloth, staring out between the spokes of a spinning wheel. A black and white photograph from Life Magazine of a nuclear test, “Yucca Flat, Nevada, 1953.” A Georgia O’Keefe print of a patch of sky seen through the hollow of a pelvic bone bleached white in the sun.

An agate marble that shone a dusky silver-red, the cracked blade of a pocket knife, the ID bracelet from the hospital, five or six rings she often wore. She had been assigned a self-portrait in her studio class. She took a wire coat hanger and undid one end, twisting it into a spiral, then hung these objects from it with varying lengths of string. Her instructor gave her a B+, saying the sculpture was too abstract, lacked feeling, it was only a cage. But I found it beautiful, ethereal. It had a certain asymmetry to the eye, yet every part balanced perfectly. I hung it in the window and would watch from my bed as it spun gently in the breeze, a kind of armature, netting her heart as the dull metals caught the light.

Someone drinking tea at the table next to mine, the scent of jasmine. A cover at a local bar, vaguely familiar, disguised at first by the unusual rhythm but the words seeping in, Well it’s a marvelous night for a Moondance, With the stars up above in your eyes … A certain quality of light, granular and blue, at dusk, when there’s been heavy rain. What sneaks up on me when I’m least expecting, takes my breath, catches me unaware.

Her photographs. The faces like stonefish, floating above the blue afghan on her bed. Photographs of rock pools in San Francisco, always with my sneaker or my hand along the rim for scale. The series she called “Camera Obscura.” This involved photographing round objects in square containers, or square objects in round containers (“Even Aristotle questioned how the sun could make a circular image when it shined through a square hole,” she explained), or in making her body look like what it wasn’t — an arum lily, a marble column.

A weekend in late January, a gray, cold day, everything slightly damp. She took us all to Chicago as a thank-you for our help. We walked along the Chicago River, and climbed through a sort of hollowed cliff, searching for toe-holds in the dirt and overgrown roots, coming out at the base of the DuSable Bridge. She asked us to photograph her, sitting by the water underneath the bridge; peering through what I think was a hollowed-out log. We found a metal ladder used by a work crew that was screwed to the wall of the bridge and climbed from the darkness below up onto a wind-filled platform. She balanced there, a white fragile body on the ledge of the bridge’s dark eye, her arms raised so that she appeared to hold up the flat roof — a caryatid. A photograph taken from above as she clung to the ladder, her sharp face and round shoulder emerging through the lens. After an hour, shivering with cold, we had to stop and find warmth. We sat huddled together on the platform below the bridge as protection from the wind and drank from a thermos of tea. Cole draped a wool blanket over our knees and slowly a little warmth came. I tasted rain on my lips. Shallow waves echoed in the stone hollow, and entered the spaces between words. I would’ve stayed there, enduring the discomfort, dampness seeping in at the small of our backs, curling up in the bone. She jumped up and handed me the Thermos, the cold air digging deeper into my bones. “Look at my skin — it’s blue,” she said, and laughing, held her hands out to show me. She stood up, her feet still bare, cracked and bleeding a little from the crushed stones, to spin around and around with a kind of heavy grace on the dirt, then ran across to the far wall and pressed herself, her palms and her cheeks, against it. This is what I most remember. An ability to metamorphose, to sink into her environment, to embrace it, smudges of ink or clay on her hands, her cheekbone. Pressed against the curved wall of the base. Maybe her trace is there still. She pulled me up, and we both leaned out over the ledge, reaching out our hands to catch the drops of rain just starting to fall.

She told us later that she had lost the film. And then, even later, that she had found the film, but that none of the photographs had turned out.

What’s left behind.

A taste for pistachios at odd hours. A paperback I’d lent her on the beat poets, boldly underlined in red. A surprising knowledge of marine geology. Tapes of Van Morrison. Memory hollowed by time.

When the film is finally unwound in the red light of the dark room and dipped in the chemical bath, the exposed silver-halide particles turn into silver, a black metal. The dark areas in the released image carry the least trace of silver and appear transparent while the light areas appear opaque. The image is transferred from the negative to a sheet of light-sensitive photographic paper. As the transferred image is dipped once again in the chemical bath, the areas of darkness and light are reversed. She appears slowly before your eyes: a sharp face peering up at you, her round shoulders, luminescent, shining out of the dark square, as if her image has been captured at the moment of birth. The Mohists (after the philosopher Mo Ti, 470-391 B.C.E.) knew and taught that objects reflect light, and called this “shining forth.”

Shining forth. What a perfect description of the lingering effect of her attitude and grace.

broken hallelujahs

Shortly after my sister Polly passed away, I went through a brief, albeit tumultuous, period when I sensed that my prayers bounced off the church ceiling or my bedroom at night. Or if I was outside, perhaps they floated up a ways but then drifted down, like helium balloons when the buoyant gas leaked out.

It was as if all my prayers were just coming back to me as echoes of myself — no better, no higher, revealing nothing divine. At best, they might make me a better person, if I didn’t misguide myself in Jesus’ name.

But where was Jesus? Was it possible to reach Him at all? There was little point, I thought, in just bouncing prayers off ceilings.

At a retreat one summer night, we sang “Just As I Am.” Somehow, without any trigger whatsoever, I found myself careening over an abyss that can only be described as the absence of the Lord — certainly not a fear of hell or anything of that sort, just an incredible sense of a vast universe and all eternity and me alone in the silence and the dark.

I thought about that song that evening, and I prayed as I had never before done. I surrendered and I sought. I fell into that abyss of all alone. If there was a Lord at all, I would fall until He caught me up out of the emptiness, and I would not grab for anything to keep me from that end, not one straw of will or reason.

It was long after midnight when utter emptiness and deepest desire were displaced in a moment. This is where words fail. Completely. The spiritual presence which came to me was simply beyond anything I’d known or was capable of conjuring or can find language to explain, then or now. Light is an apt metaphor. Love was the essence. Tremendous reassurance. And revelation — of the essential goodness of being and all things. An untying of every twisted little knot of pain or sorrow or angst in my soul. A certain knowledge that the perceived necessity of our living as twisted, knotted creatures was indeed an illusion, a lie from the Enemy that comes from living in a world in which the Divine is partly (and sometimes almost completely) veiled. The knowledge that hate is superfluous and love is a divine gift to be shared without limit or end.

What I needed to know of Jesus to live a Godly life came to me that night, as palpable presence and revelation. I haven’t always fully lived up to that revelation, but there’s no question of me denying my Savior, not ever. I can’t disbelieve what I encountered. It’s helped to make me who I am.

Leonard Cohen’s haunting anthem Hallelujah always sounds like notes of truth for me. He writes,

There’s a blaze of light

in every word,

it doesn’t matter which you heard,

the holy or the broken Hallelujah

Mostly, we hear broken Hallelujahs. Our sermons, our songs, my words on this page — all these are broken Hallelujahs because we simply can’t piece together words that serve as adequate vessels to hold and pour out the divine. And whatever we do piece together is always, well, full of us.

In our time, Hallelujah has been corrupted for political campaign slogans by those who know how to harness religion for their own ends. Hallelujah has been enslaved to intolerance and injustice in the name of a righteousness that forgets the very nature of Jesus. Hallelujah has been co-opted to serve the rich and fleece the poor, in an inversion of the beatitudes.

And perhaps nowhere is this hijacking as evident at the moment as in our own backyards.

There’s violence that confronts us around every corner, from the misguided and broken young girl who picked up a gun and entered a church preschool in an evil attempt to quiet her personal demons to the physical assaults on a young collegiate swimmer who speaks undeniable truths regarding fairness and common human decency.

The Enemy creates a wall of noise and visual static in an attempt to silence our faith and there are times when it seems as though he’s winning the battle.

But we of faith know how this ends.

That night at the retreat, Jesus spoke to me very clearly and decisively: pay close attention. Listen. Learn. Witness, for them; for Me.

All around us are stories of unparalleled grace and compassion under the most extreme circumstances; stories of people in schools and theaters and offices who put their personal safety aside to reach out to the slightly injured and severely wounded, oblivious to the danger around them.

Oblivious to the evil around them.

What these people collectively did (and what they continue to do) is nothing short of astonishing. There are stories upon stories of ordinary men and women who performed extraordinary acts of courage and compassion for their fellow man. Day after day, more definitive lines are being drawn, and neither the deeds of Satan nor the shadow of death are plausible matches for these profoundly selfless acts of grace.

My little children, let us not love in word or in tongue, but in deed and in truth.

— 1 John 3:18

And love one another in deed and in truth they did. They do.

It’s time, and perhaps this is perpetually so, for us to examine our broken Hallelujahs, to sort out our blazes of light from our flawed humanity. Let’s all make today a new chapter in our lives, and renew our promise to Jesus to do just that.

sharing oxygen

Someone’s hand was on my shoulder. In the distance, I heard words forming, nearly obliterated by the rising sound of water rushing, cascading into my head, saying, “I’m so very sorry about your sister.” And, “I had no idea she was that ill.” Or, “How are you? If there’s anything I can do ...”

My sister Judy had passed away quickly, unexpectedly, and I was struggling to make sense of it all. I stood in the back of the room for quite a while, too uncomfortable to make my way to her casket. I talked with my family, greeted old friends, and chatted briefly with others who had come to pay their respects.

In a genuinely affectionate manner, I’d become the object of other people’s discomfited pity. I neither disparaged nor rejected the sympathies; they were meant honestly, and it was no one’s fault that human language so poorly serves unfeigned emotion.

When I finally made my way to my sister’s casket, I thought about a whitewater rafting trip I’d taken years ago with a group of friends to New River Gorge in West Virginia. Although they were seasoned rafters, it was my first time (and yes, I’ll blame it on being a very pale redhead who hates the sun). We were in class three and four rapids, pushing hard into the roil. Suddenly our bow got caught in an undertow, stopping us cold; as the raft shuddered violently, the rear flipped upwards throwing several of us out. I landed on my knees on a gravel bar, tumbling into the water, out of control and searching for oxygen. I briefly panicked not knowing where my friends were, but as I came up, I saw them being pulled into the raft. Relieved, I did as instructed: I relaxed back in the water, fifty yards downstream from the ejection, and more moderately buffeted, hearing shouts and conversation garbled through the garrulous water.

Mildly surreal, disconnected beneath the hazy sky and above the sunken ground, I sucked in air that I’d read somewhere had been breathed by Jesus, Einstein, Newton, Aristotle, and untold others.

Suddenly, another of my sister’s friends came upon me and pulled me back to that late November day. As I considered the weight and warmth of her hand upon my shoulder, the softness and depth of the eyes that evaluated my own, the words pouring in to which I made a conditioned, autonomic response, I inhaled sharply and remembered that I no longer shared that oxygen with her.

dianeisms

Jack Kerouac’s On The Road is my favorite book. If you read it and don't get it, you'll never understand me.

My mouth can hold exactly 3.25 Peeps. Do not ask me how I know this.

I love poetry and am fascinated by words.

If I had my choice, I’d teach creative writing to college students.

I’m an incurable insomniac.

I enjoy intelligent discussions on almost any topic. At times, I enjoy stupid conversations even more.

I like to think I’m eternally patient with children and the elderly. My family would probably disagree.

I don’t have a middle name.

I think Caro Mio Ben is the total of all that's grand and wonderful about music, distilled down into three minutes of sheer perfection.

I’m completely mesmerized by precision craftsmanship. I can stare at the clockwork of a Breguet or Audemars Piguet for hours.

I get teary every time I hear Nessum Dorma. Every. Time.

I’m a list maker. I have lists everywhere and for everything. (This list, for instance? Yeah, it was on a list.)

I’m a gadget freak.

The most attractive aspect of a person to me is their level of compassion.

Give me a good book and you won’t see me for hours.

I’ve been told that my best attribute is my commitment to Jesus.

The best compliment I ever received was, “In every single way, you’ve made my life better.”

I think a lot of truth is said in jest.

I don’t like it when people tell me what to do.

I don’t understand how there can be such a thing as a galactic constant.

I love being in a crowd. The more people the better. I attribute this to having grown up in a large family.

I look at people too much. Someone charitably described this as looking at people like an artist — except when I watch them, I’m not thinking about how I could draw them, I’m describing them. Usually. Sometimes I’m simply enjoying the sight of them.

If I see an Elvis or Godzilla movie on television, I have to watch it. Have to.

I can’t sing. At all. It doesn’t stop me.

Winter is my favorite season.

Pancakes are my favorite breakfast food, followed closely by Capt’n Crunch cereal.

I always keep a small amount of bubble wrap on my desk where I write. I pop a row or two whenever I'm in deep thought.

I believe in miracles.

i couldn’t be

It's always amazing to me how the minds of children work.

After spending yesterday at the zoo, my friend’s grandson Aras has become quite interested in all things creepy-crawly. Spiders. Snakes. Ticks. Scorpions. Centipedes. You name it — if it's sure to make you feel itchy and it'll freak out the girls, color him curious.

As a result, I wasn't at all surprised when he had his grandmother FaceTime me last night so that he could show me several books about animals and insects that he'd purchased before leaving the zoo.

Fast-forward to this morning. Smack-dab in the middle of another FaceTime call to continue our spider discussion, he paused on the subject long enough to pose a question: "What if days started with different letters?"

He then proceeded to ramble off the following: Ariday, Briday, Criday, Driday, Eriday, Friday (“Nevermind. It’s already taken.”), Griday, Hriday, Iriday, Jriday, Kriday, Lriday, Mriday, Nriday, Oriday, Priday, Qriday, Rriday, Sriday, Triday, Uriday, Vriday, Wriday, Xriday, Yriday, and Zriday.

Ahh, the wonder of being a child.

Eager to end my tour into arachnophobia, I explained that sadly, only Ariday (day of little or no rain), Driday (yet another day of little or no rain), and Triday (day of fulfilling your potential) made sense. My always-spot-on-for-a-five-year-old logic was evidently convincing enough that he abandoned that method of thought and went back to reading his books.

Later, over a stack of pancakes, they called once again with yet another question. Always the inquisitive one, he asked, "You like to write books and look at things, but what couldn’t you be?

"Yes," his grandmother chimed in, "what couldn't you be?"

What couldn't I be??

[This is the moment where you picture me looking up from the computer, into the sky, and the image becomes all wavy and dreamlike as I imagine exactly what I couldn't do.]

I then explained that I couldn’t be a lot of things.

I couldn’t be your money launderer. Or your launderer for that matter. Any kind of laundering, I'm not doing. If it requires soap or detergent or some sort of Snuggle fabric softener or involves the depositing of money into one account in preparation of spending it from another account in preparation of buying corn meal that I can then sell on the corn meal black market in an attempt to make dirty money clean again — I have to decline. There’s no way I could do this. No way, no how.

I couldn’t be your hand-latched lifter-upper. No matter what’s in that tree or over that wall or up in the attic, there’s something I just can't deal with when you ask me to latch both hands together so I can form a human step for your dirty shoe. Use a step ladder. Someone else’s back. Find a small child. But I can’t support the use of my hands for your feet. Nope, can’t do it.

I couldn’t be your new recipe guinea pig. No matter how well you think you follow the recipe and no matter how perfect it looks, I can’t be the girl who takes the first taste. Because even if the first taste is really good, no matter what I say I'm in for a world of pain. Did I like it? Not like it enough? Did I not smile when I tasted it? Did I not sniff in the aroma and make a pleasant-looking facial expression? Did I not roll it around in my mouth long enough to taste the whole experience of your brand-new hobby? I refuse. I cannot. No sir.

I couldn’t be your high-five buddy. Nuh-uh. Although I’m fully in support of you finishing your beer, tripping a kid on the sidewalk, eating a bag of Cheetos in one big bite, or burping the alphabet — I cannot give you the hi-five. It's from a day that has passed us by, dear friend, and no matter how cool the slapping sound can be, I cannot bring myself to raise my arm in celebration of all things food, bullying, and Cheetos.

These are just some of the things I believe I couldn’t be.

I couldn’t be your backscratcher or your flat tire fixer. I couldn’t be your back waxer or your dog groomer. I couldn’t be your racquetball buddy or your workout spotter. I couldn’t be your haircutter or your neck trimmer. I couldn’t be your comic sidekick, the creator of your theme music, the gal who says nothing even though you stink, your “please watch my vacation video” buddy, your shot-giver, your furniture mover, your cookie-snatcher, your floor-sweeper, or your friend who enjoys hearing you read your poetry.

There are some things that you'd probably not want me to be anyway.

I couldn’t be your food chewer, your backseat driver, your fruit juicer, your lazy trainer, your “bad with numbers” accountant, your “the man is the King of the Castle” marriage counselor, your hockey coach or your live-in, out of work, unemployed pool girl.

Sure, there are more things that I couldn’t be.

But with the world the way it is, and the lack of motivation already hovering above society like an evil that cannot be defeated — is it really worth telling you about how I can't do this and I can't do that? Is it really worth denying myself potential chapters in my life just because a question was asked over a mound of pancakes?

I think not.