sight unseen

… I believe electronic books are akin to desecrating the flag.

About a month ago, I received a call from a friend in Canada. He’d just returned from Haiti after serving a two-year stint in the Peace Corps, and he wanted to share something with me.

The people there, he said, are suspicious of folks with disabilities, and he encouraged me to be extra careful while on an upcoming trip. “There’s something especially troubling to Haitians about the blind,” he said, “so please take good care.”

Huh. The Haitians are blindists. Who knew?

As for the wish to be safe and take care, I assured him that it wouldn’t be a problem. First of all, I was going to Ohio, not Haiti. Secondly, even if I had chosen the Caribbean over the Midwest, it’s not like I’d have swung my stick at ‘em like piñatas. Contrary to what some believe, being visually impaired hasn’t made me a complete nitwit.

I spent the remainder of the day packing my travel essentials (Bible, iPads, journal, favorite pens and pencils, Kerouac, and several pairs of glasses and sunglasses), and neatly organizing my bag.

Only one person questioned my selections. Cole, Jayne’s latest new boyfriend, seemed confused as to why I just didn’t download a digital copy of the books onto a device.

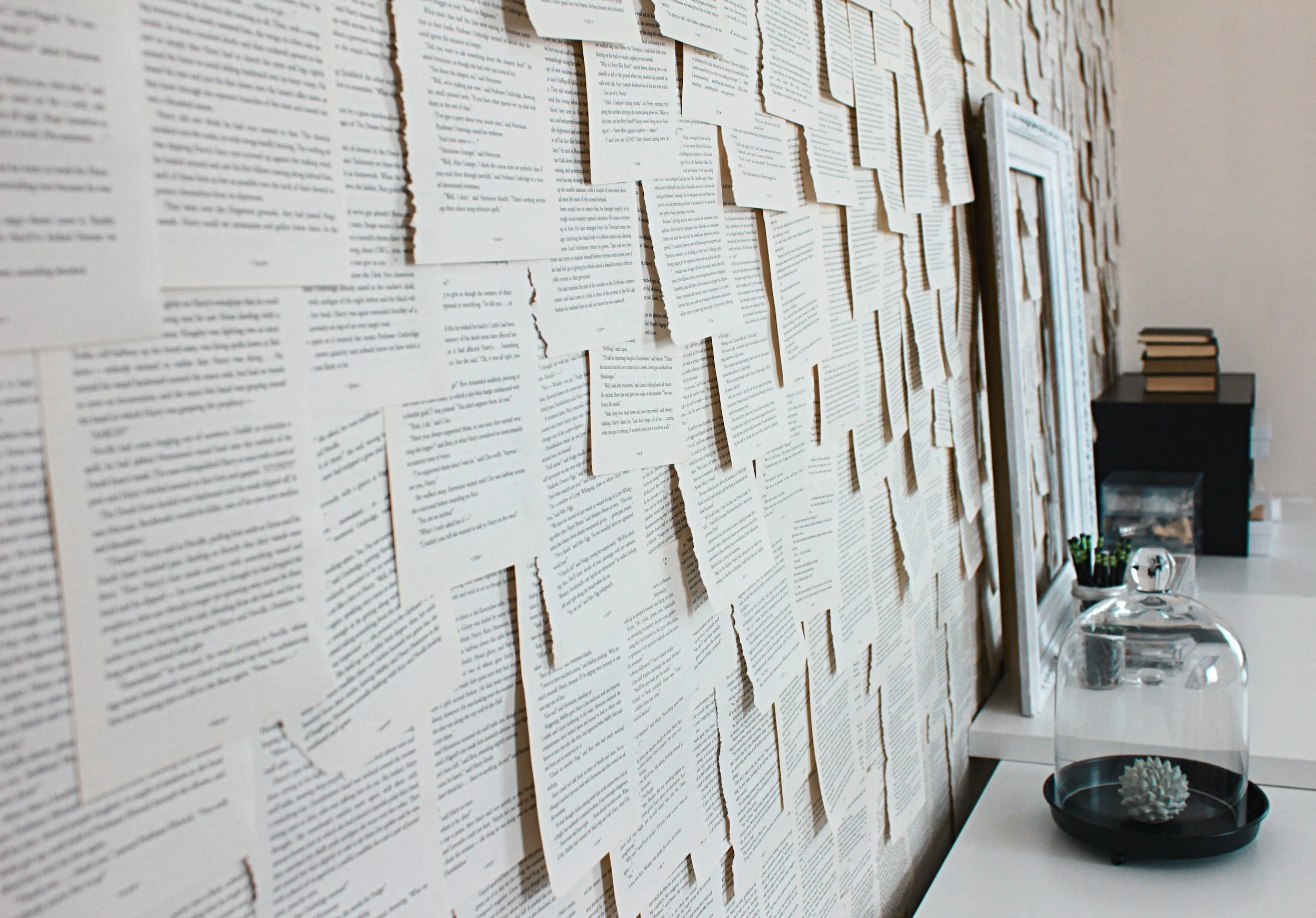

“If you have to ask, you’ll not understand,” I said, “but I believe electronic books are akin to desecrating the flag.” I then shot a disapproving look in what I believed was Jayne’s general direction and quickly dismissed him. I can’t be bothered with dolts who don’t appreciate the community of the written word — an arrogance defined many years ago by a dear friend named Jacob, and bestowed upon me by the man himself.

Jacob loved words and books, and he lived his life in their immediate presence. Indeed, his life and the element of language in which he lived were indivisible. I cannot imagine his existence — a man made of flesh and blood, a man who walked in the sunlit streets of Europe, chatted with friends, ate good food and drank good wine, who slept and dreamed in the light of the moon — unless I remember as well the language in which he placed these things. His presence in my life taught me to understand that our human experience, however intense it may be, is truly valid only in proportion to its expression in words.

Expression is a word and a concept in which he had complete faith. He believed that poetry was expression and that it was founded upon aesthetics. Consequently, in our time and place, we’re distracted by the notion of communication, which is perhaps inferior to expression. I believe Jacob thought so, anyway.

I say all that to say just this: while I’m legally blind, words nonetheless allow me to see farther into the world than most sighted people. Little by little, I’ve come to realize the strange irony of events in the past few years. While others often think of Paradise as a garden or a palace, I’ve come to imagine it as a kind of library, with me at the center of billions of words in thousands of languages.

That’s Paradise. On Earth, however, I’m unable to make out the title pages and the spines without the aid of technology. In the early stages of my impairment, I felt anger at my God who granted me books and blindness at one touch. Now I feel neither self-pity nor reproach, as I’m compelled to make it the cornerstone and definition of my being. In doing so, I’m reminded of Homer, also blind, who made as much of a balance between oral tradition and the history of the Trojan wars.

As important as books are (and as important as writing is), there’s yet another, a fourth dimension of language that’s just as important and that’s older and more nearly universal than writing. This other side of the miracle of language is the oral tradition, which encompasses the telling of stories, the recitation of epic poems, the singing of songs, the making of prayers, the chanting of magic and mystery, the exertion of the human voice upon the unknown — in short, the spoken word.

In the history of the world, nothing’s been more powerful than the ancient and irresistible tradition of vox humana. This tradition is especially and above all the seat of the imagination, and the imagination is a kind of divine blindness in which we see not with our eyes, but with our minds and souls … in which we dream the world and our being in it.

My friend’s stories of his service in the Peace Corps have proven to be a voyage of faith for me in more ways than one. Not only are each of us able to serve as the hands and feet of Jesus as we build His communities and spread the joy of His gift of salvation, but I’m living proof to the infirm that we’re defined not by our inabilities, but by our promise to look onward and, most importantly, upward.

Our resolute belief that we can do all things through Christ who strengthens us, diminishes our imperfections, and harnesses His love for us like a mighty beacon of light for all to see and behold.

With that, is it any wonder that I’ve found all color and brilliance in words and languages, spoken or felt, through His grace?

a legacy of love

On May 3, 1991, my father died. I was holding his hand. He'd been diagnosed with inoperable cancer just a month earlier.

Until the moment of his death, I never really believed it would happen. But there I was, kneeling on the floor beside him, whispering my goodbyes in his ear, telling him for the last time how much I loved him, hoping — praying, actually — that he could still hear me. I hated the scene, but I was powerless to change it.

I realize now that as my father lay dying, I learned about living. I saw my dad, a 74-year-old man who had become but a child, and I thought at first that he’d been stripped of his dignity and meaning. But what I've ultimately come to view is a portrait of a man who refused to relinquish his humanness and decency.

The tragedy of cancer isn’t a new topic. To date, nearly 60 million American families have survived the nightmare of losing a loved one to this disease. And as the statistics continue to multiply, so, too, does the fear that surrounds them.

I consider myself a cancer survivor. And although the disease hasn’t afflicted my body, it’s nonetheless made an undeniable and unforgettable impression on my soul. I understand that although the plight of my family is but a small fraction of the number of cancer cases reported, it forms a mosaic portrait of the face of cancer worldwide. It’s a young face, for the most part , one that shares a common loss of the best years life has to offer. It’s also a face that’s representative of a life cut short too soon, representing, almost, the death of the American family.

Seeing my father fall to cancer reminds me still that the victims are ours — our kin, our colleagues, our neighbors, and our friends. The great French writer Albert Camus, visiting America, called it “this great country where everything is done to prove that life isn't tragic.” I think the same is true across the globe. Our habit is optimism; we're unaccustomed to an illness that resists the magic of our medicine and we've too often held ourselves apart from its sufferers. But our response to cancer has in important ways defined us as a society. “No one will ever be free so long as there are pestilences,” Camus wrote in his novel “The Plague.” My father and the rest of the fallen bear silent witness to the fact that we're still hostage to cancer.

Fortunately, Dad was an extraordinary individual with a keen sense of realization. When he became ill, he began to see all sorts of things going on around him that were a reaction to and a consequence of his disease; he began to feel the pressures of a world not prepared to deal with cancer. So, as he was dying, he decided to leave a legacy for others by talking about his experiences in trying to cope with this painful reality. My father wanted people to see the human side of cancer: the faces, the emotions, the tears, and the secret doubts. He attempted to help demystify the disease by personalizing it and showing its human impact in a non-threatening and honest manner.

My family’s apprehensions regarding Dad’s disease were soon erased; the support and unconditional love he received as he grew weaker and less able to help himself were indeed impressive. But perhaps more touching was that the people involved with our struggle with his illness — those who surrounded him and shared in his last days — provided a model for compassionate care of terminal patients.

Watching my father die was one of the hardest things I've ever had to do. And I know in my heart that I'll never forget what I saw and heard on the day that he died. But my father gave me life, and he gave me love. And in return, I made a promise to myself to be with him when he died. I felt as though I somehow needed to mark the end. I wanted to be there to wipe his brow, to hold his hand, and to comfort him as best I could. The funny thing is, it was he who did the comforting; it was he who tried so desperately to make sense of the situation. And it was he who gave great meaning to his life and death by reaching out to those around him. My father was a wealth of knowledge and strength. And at a time when denial and self-pity would've been both encouraged and accepted, he rose to the challenge and — once and for all — displayed the indomitable strength of the human spirit.

My dad once told me that although she had been gone more than half a century, he thought of his mother every single day. He also admitted that while he was incredibly sad to be leaving his family, he was so looking forward to seeing her in Heaven and giving her a long-overdue hug.

I still cry each time I think about that conversation, although the meaning of the tears has transformed over time. Where they were once a symbol of my immense grief, they've ultimately come to reflect a reluctant acceptance that until a cure is found, more sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, will lose an integral part of their lives to this horrid disease.

My dad was a remarkable man, full of humility and God’s grace, and I think I can safely say that nothing would’ve pleased him more than to see the living legacy of his family. He would've been thrilled beyond words to know that the spirit of his love and laughter and courage continues to weave its way through the lives of my siblings and the next generations.

So today, I'll remember my father’s deep and unabiding faith in God Almighty and his tremendous love for his family, and I'll take great comfort in knowing that I've spent the day in a way he would relish — in a celebration of life.